|

The way in which Congress develops tax and spending legislation is guided by a set of specific procedures laid out in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. The centerpiece of the Budget Act is the requirement that Congress each year develop a "budget resolution" setting overarching limits on spending and on tax cuts. These limits apply to legislation developed by individual congressional committees as well as to any amendments offered to such legislation on the House or Senate floor.

The following is a brief overview of the federal budget process, including:

- the President's budget request, which kicks off the budget process each year;

- the congressional budget resolution - how it is developed and what it contains;

- how the terms of the budget resolution are enforced by the House and Senate; and

- budget "reconciliation," a special procedure used in some years to facilitate the passage of spending and tax legislation.

Step One: The President's Budget Request

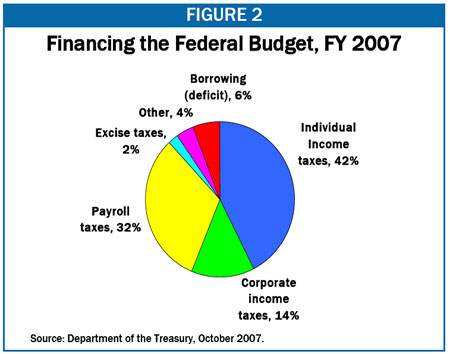

On or before the first Monday in February, the President submits to Congress a detailed budget request for the coming federal fiscal year, which begins on October 1. This budget request, developed by the President's Office of Management and Budget (OMB), plays three important roles. First, it tells Congress what the President believes overall federal fiscal policy should be, as established by three main components: (1) how much money the federal government should spend on public purposes; (2) how much it should take in as tax revenues; and (3) how much of a deficit (or surplus) the federal government should run, which is simply the difference between (1) and (2).

Second, the budget request lays out the President's relative priorities for federal programs - how much he believes should be spent on defense, agriculture, education, health, and so on. The President's budget is very specific, and recommends funding levels for individual federal programs or small groups of programs called "budget accounts." The budget typically sketches out fiscal policy and budget priorities not only for the coming year but for the next five years or more. It is also accompanied by historical tables that set out past budget figures.

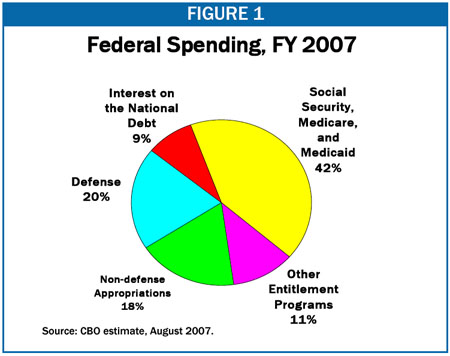

The third role that the President's budget plays is to signal to Congress what spending and tax policy changes the President recommends. The President does not need to propose legislative change for those parts of the budget that are governed by permanent law if he feels none is necessary. Nearly all of the federal tax code is set in permanent law, and will not expire. Similarly, more than one-half of federal spending - including the three largest entitlement programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security) - is also permanently enacted. Interest paid on the national debt is also paid automatically, with no need for specific legislation. (There is, however, a separate "debt ceiling" which limits how much the U.S. can borrow. The debt ceiling is periodically raised through separate legislation.)

The one type of spending the President does have to ask for each year is:

- Funding for "discretionary" or "appropriated" programs, which fall under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. Any discretionary program must have its funding renewed each year in order to continue operating. Almost all defense spending is discretionary, as are the budgets for K-12 education, health research, and housing, to name just a few examples. Altogether, discretionary programs make up about one-third of all federal spending. The President's budget spells out how much funding he recommends for each discretionary program.

The President's budget can also include:

- Changes to "mandatory" or "entitlement" programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and certain other programs (including but not limited to food stamps, federal civilian and military retirement benefits, veterans' benefits, and unemployment insurance) that are not controlled by annual appropriations. For example, when the President proposed adding a prescription drug benefit to Medicare, he had to show a corresponding increase in Medicare costs in his budget, relative to what Medicare would otherwise be projected to cost. Similarly, if the President proposes a reduction in Medicaid payments to states, his budget would show lower Medicaid costs than projected under current law.

- Changes to the tax code. Any presidential proposal to increase or decrease taxes should be reflected in a change in the amount of federal revenue that his budget expected to be collected the next year or in future years, relative to what would otherwise be collected.

To summarize, the President's budget must request a specific funding level for appropriated programs and may also request changes in tax and entitlement law.

Step Two: The Congressional Budget Resolution

After receiving the President's budget request, Congress generally holds hearings to question Administration officials about their requests and then develops its own budget resolution. This work is done by the House and Senate Budget Committees, whose primary function is to draft the budget resolution. Once the committees are done, the budget resolution goes to the House and Senate floor, where it can be amended (by a majority vote).[1] It then goes to a House-Senate conference to resolve any differences, and a conference report is passed by both houses.

The budget resolution is a "concurrent" congressional resolution, not an ordinary bill, and therefore does not go to the President for his signature or veto. It also requires only a majority vote to pass, and is one of the few pieces of legislation that cannot be filibustered in the Senate.

The budget resolution is supposed to be passed by April 15, but it often takes longer. Occasionally, Congress does not pass a budget resolution. If that happens, the previous year's resolution, which is a multi-year plan, stays in effect.

- What is in the budget resolution? Unlike the President's budget, which is very detailed, the congressional budget resolution is a very simple document. It consists of a set of numbers stating how much Congress is supposed to spend in each of 19 broad spending categories (known as budget "functions") and how much total revenue the government will collect, for each of the next five or more years. (The Congressional Budget Act requires that the resolution cover a minimum of five years, but Congress sometimes chooses to develop a 10-year budget.) The difference between the two totals - the spending ceiling and the revenue floor - represents the deficit (or surplus) expected for each year.

- How spending is defined: budget authority vs. outlays. The spending totals in the budget resolution are stated in two different ways: the total amount of "budget authority" that is to be provided, and the estimated level of expenditures, or "outlays." Budget authority is how much money Congress allows a federal agency to commit to spend; outlays are how much money actually flows out of the federal treasury in a given year. For example, a bill that appropriated $50 million for building a bridge would provide $50 million in budget authority in the same year, but the bill might not result in $50 million in outlays until the following year, when the bridge actually is built.

Budget authority and outlays thus serve different purposes. Budget authority represents a limit on how much funding Congress will provide, and is generally what Congress focuses on in making most budgetary decisions. Outlays, because they represent actual cash flow, help determine the size of the overall deficit or surplus.

- How committee spending limits get set: 302(a) allocations. The report that accompanies the budget resolution includes a table called the "302(a) allocation." This table takes the total spending figures that are laid out by budget function in the budget resolution and distributes these totals by congressional committee. The House and Senate tables are slightly different from one another, since committee jurisdictions vary somewhat between the two chambers.

The Appropriations Committee receives a single 302(a) allocation for all of its programs. It then decides on its own how to divide up this funding among its many subcommittees, into what are known as 302(b) sub-allocations. (In 2006, the Committee ultimately subdivided its total among 11 different appropriations bills.) The various committees with jurisdiction over mandatory programs each get an allocation that represents a total dollar ceiling for all of the legislation they produce that year.

The spending totals in the budget resolution do not apply to the "authorizing" legislation produced by most congressional committees. Authorizing legislation typically either changes the rules for a federal program or provides a limit on how much money can be appropriated for it. Unless it involves changes to an entitlement program (such as Social Security or Medicare), authorizing legislation does not actually have a budgetary impact. For example, the education committees could produce legislation that authorizes a certain amount to be spent on Title I reading and math programs for disadvantaged children. However, none of that money can be spent until the annual Labor-HHS appropriations bill - which includes education spending - sets the actual dollar level for Title I funding for the year, which is frequently less than the authorized limit.

Often the report accompanying the budget resolution contains language describing the assumptions behind it, including how much it envisions certain programs being cut or increased. These assumptions generally serve only as guidance to the other committees and are not binding on them. Sometimes, though, the budget resolution includes more complicated devices intended to ensure that particular programs receive a certain amount of funding. For example, the budget resolution could create a "reserve fund" that could be used only for a specific purpose.

The budget resolution can also include temporary or permanent changes to the congressional budget process. For example, the fiscal year 2006 budget resolution contained a provision preventing the Senate from considering legislation that would increase entitlement costs by more than a very small amount during the period from 2016 through 2055, and created a point of order - which can be waived only by the vote of 60 Senators - to enforce that prohibition.

How Are the Terms of the Budget Resolution Enforced?

The main enforcement mechanism that prevents Congress from passing legislation that violates the terms of the budget resolution is the ability of a single member of the House or the Senate to raise a budget "point of order" on the floor to block such legislation. In recent years, this point of order has not been particularly important in the House because it can be waived there by a simple majority vote on a resolution developed by the leadership-appointed Rules Committee, which sets the conditions under which each bill will be considered on the floor. However, the budget point of order is very important in the Senate, where any legislation that exceeds a committee's spending allocation - or cuts taxes below the level allowed in the budget resolution - is vulnerable to a budget point of order on the floor that order requires 60 votes to waive.

Appropriations bills (or amendments to them) must fit within the 302(a) allocation given to the Appropriations Committee as well as the Committee-determined 302(b) sub-allocation for the coming fiscal year. Tax or entitlement bills (or any amendments offered to them) must fit within the budget resolution's spending limit for the relevant committee or the revenue floor, both in the first year and over the total multi-year period covered by the budget resolution. The cost of a tax or entitlement bill is determined (or "scored") by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, which measures it against a budgetary "baseline" that projects entitlement spending or tax receipts under current law.

The Budget "Reconciliation" Process

From time to time, Congress chooses to make use of a special procedure outlined in the Congressional Budget Act known as "reconciliation."[2] This procedure was originally designed as a way to force committees to produce spending cuts or tax increases called for in the budget resolution. While the reconciliation process was intended as a deficit-reduction mechanism, it has been used several times during the Bush Administration (in 2001, 2003, and 2006) to pass costly tax-cutting legislation as well.

- What is a reconciliation bill? A reconciliation bill is a single piece of legislation that typically includes multiple provisions (generally developed by several committees) all of which affect the federal budget - whether on the mandatory spending side, the tax side, or both.[3] A reconciliation bill is the only piece of legislation (other than the budget resolution itself) that cannot be filibustered on the Senate floor, so it can pass by a majority vote.

- How does the reconciliation process work? If Congress decides to use the reconciliation process, language known as a "reconciliation directive" must be included in the budget resolution. The reconciliation directive instructs various committees to produce legislation by a specific date that meets certain spending or tax targets. (If they fail to produce this legislation, the Budget Committee Chair generally has the right to offer floor amendments to meet the reconciliation targets for them, which is enough of a threat that committees tend to comply with the directive.) The Budget Committees then package all of these bills together into one bill that goes to the floor for an up-or-down vote, with only limited opportunity for amendment. (Sometimes the tax provisions and the entitlement provisions are considered in two separate bills.) After the House and Senate resolve the differences between their competing bills, a final conference report is considered on the floor of each house and then goes to the President for his signature or veto.

- Constraints on reconciliation: the "Byrd rule." While reconciliation enables Congress to bundle together several different provisions affecting a broad range of programs, it faces one major constraint: the "Byrd rule," named after Senator Byrd of West Virginia. This Senate rule makes any provision of (or amendment to) the reconciliation bill that is deemed "extraneous" to the purpose of amending entitlement or tax law vulnerable to a point of order. If a point of order is raised under the Byrd rule, the offending provision is automatically stripped from the bill unless at least 60 Senators vote to waive the rule. This makes it difficult, for example, to include any policy changes in the reconciliation bill unless they have direct fiscal implications. Under this rule, authorizations of discretionary appropriations are not allowed, nor are changes to civil rights or employment law, for example. Changes to Social Security also are not permitted under the Byrd rule.

In addition, the Byrd rule bars any entitlement increases or tax cuts that cost money beyond the five (or more) years covered by the reconciliation directive, unless these "out-year" costs are fully offset by other provisions in the bill. This is a central reason why Congress made the 2001 tax cuts expire by 2010, rather than making them permanent.

End Notes:

[1] For more than 20 years, the House leadership has prevented the budget resolution from being amended freely on the floor. Instead, the Rules Committee - an arm of the leadership whose role is to develop resolutions that set the terms for floor debate - has generally allowed the consideration of only a few "substitute" amendments. These are alternative budgets, typically developed by the minority party or caucuses within the House that have a particular interest in budget policy.

[2] In this context, the term "reconciliation" does not have its ordinary meaning of two parties working out their differences (for example, the House and Senate are often described as going to conference to "reconcile" competing versions of a bill). Rather, it refers to the process by which congressional committees adjust, or "reconcile," existing tax or entitlement law with the new tax or mandatory spending targets called for in the budget resolution.

[3] A separate rule of the House and Senate prohibits legislation other than Appropriations Acts from providing or rescinding discretionary appropriations. On occasion this rule has been ignored and other legislation - including reconciliation bills - has included items of discretionary appropriations. |